The social evolution of cooperation

Henry Rachootin

The biological cooperation of evolution is fascinating, but it is also important to consider how cooperation emerges in social settings. The idea that biology is inherently competitive is widely believed but not particularly problematic, even if it is somewhat reductive. More often, the idea that society is or ought to be inherently competitive is a source of cruelty and ignorance, as seen in the social Darwinist movement of the early twentieth century. To remedy this, I investigate the question: what factors cause or speed up the natural emergence of cooperative behavior in a social network?

In [2], T. Ohdaira presents a model for social cooperation and selfishness. It is an evolutionary game theory networked prisoner’s dilemma model, in which a network of agents play a single round of the prisoner’s dilemma against each of their neighbors, then copy the strategy of their neighbor with the highest total score (or they don’t change, if they have a higher score than their neighbors). Successful defection is worth 1.5 the value of successful cooperation. The agents’ strategies are as simplistic as possible: they either always cooperate or always defect. The initial distribution of strategies is chosen at random, with each agent having equal odds of starting with either.

Ohdaira’s experiment adds a ‘decision cost’ to the agents’ strategies, which is a value between 0 and 1 that is subtracted from the agent’s score after playing all of their rounds, and compares the results to the same experiment without the cost. This is meant to coarsely model the fact that different people justify their decisions to cooperate or defect in more or less complex ways, which makes their deliberation cost them more or less. One strategy might involve choosing to cooperate or defect after hemming and hawing for a long time, whereas another might do so without thinking at all. The decision cost is part of the agent’s strategy so it is copied with the strategies. The costs are initially chosen at random, independently for each agent.

Ohdaira finds that the addition of decision cost allows cooperation to dominate in Barabasi Albert [2] networks more often than is would otherwise dominate, allows cooperation to dominate faster than it otherwise would in ring lattices, and only allows cooperation to spread to more of the Watts Strogatz [3] network. All of the networks he uses have an average degree of four.

I reproduce his result on the ring lattice and Watts Strogatz network with my own python implementation of his model, but refute his result on the Barabasi Albert networks. I use networks with 1000 nodes and an average degree of four. You can see my code here, or run it here.

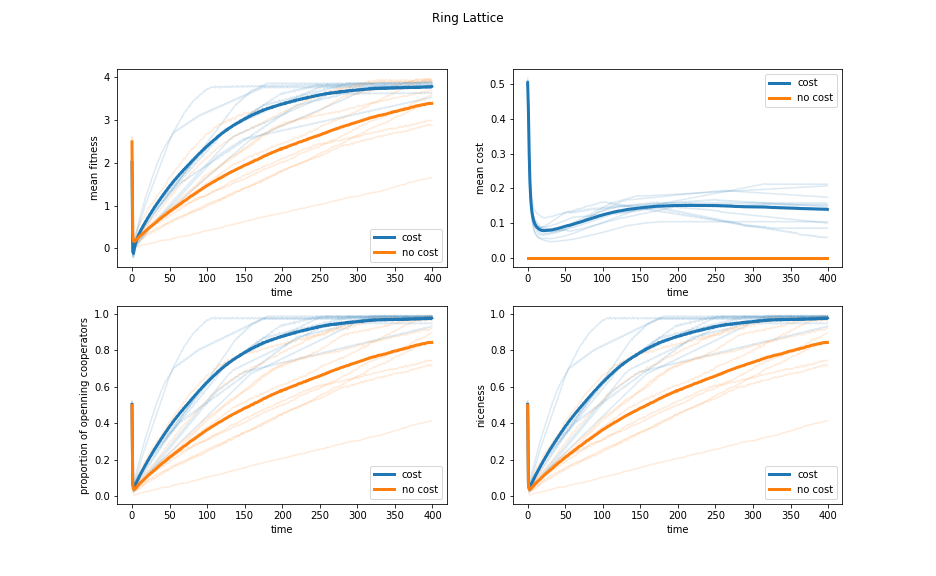

Figure 1: Evolution of the ring lattice model with and without decision costs. The pale lines show individual simulations, and the dark lines are the averages over all ten iterations. “Niceness” here refers proportion of situations in which the agents will cooperate on average. Since these agents either always cooperate or always defect, this is the same as the proportion of agents who cooperate on their first turn, as shown.

On the ring lattice, the addition of the decision cost does indeed cause cooperation to dominate faster. However it does eventually dominate anyway, and the result is somewhat unstable, needing to be averaged over many iterations of the experiment to appear. This is shown in Figure 1. In this localized network, as soon as defectors spread they create clusters of exclusively defectors with negative fitness (they score 0 for defecting, then subtract their costs). When cooperators spread, they create clusters of cooperators with positive fitness, even after subtracting their costs. This allows cooperators to invade defectors, but not visa versa.

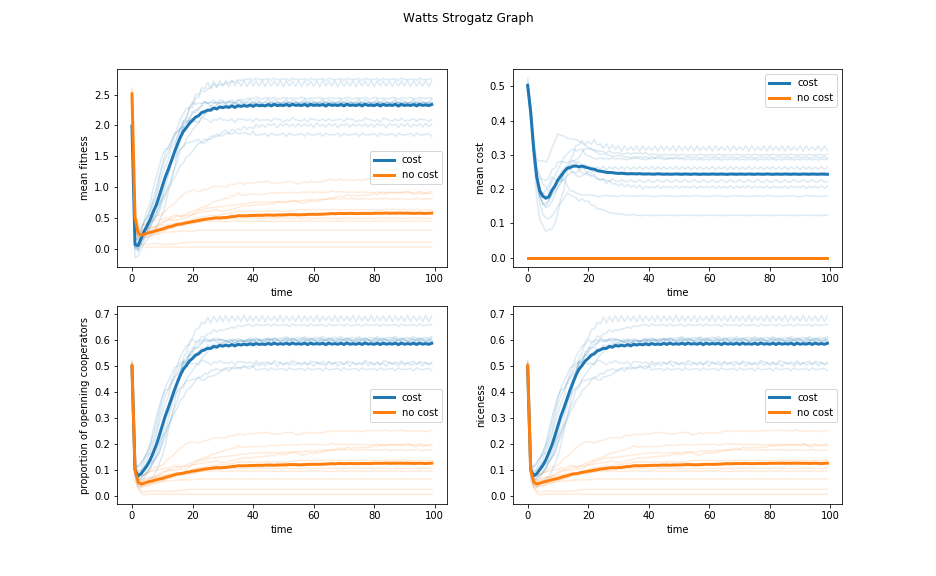

Figure 2: Evolution of the Watts Strogatz model with and without decision costs.

On the Watts Strogatz graph, neither strategy ever dominates, but the addition of decision costs shifts the equilibrium towards cooperation, and does so in every single iteration of the experiment, as shown in Figure 2. It is clear to me that the decision cost helps cooperators in this network. The same effect as in the ring lattice explains this behavior, but the bridges of the Watts Strogatz graph allow pockets of defectors to survive if they have access to multiple cooperators. These bridges also reduce the time needed for the network to reach equilibrium by reducing its mean path length.

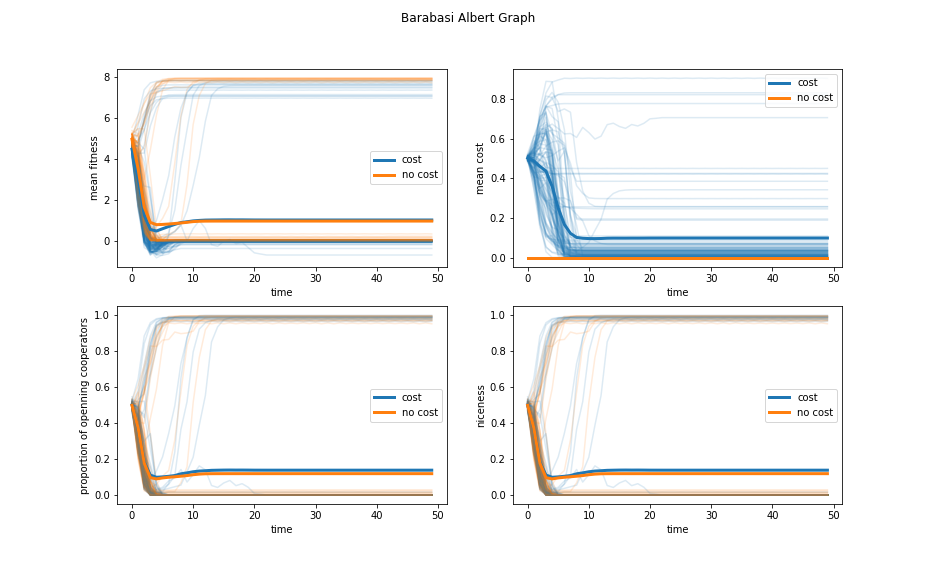

Figure 3: Evolution of the Barabasi Albert model with and without decision costs.

Ohdaira and I both find that the Barabasi Albert network reaches its equilibrium faster than either of the other networks. I take this as a sign that the system might be unstable, and so I run it over 100 iterations, compared to the 20 iterations that Ohdaira runs. As shown in Figure 3, the system is wildly unstable, and the average niceness is nearly identical with or without decision costs. I suspect that this is due to the high-degree nodes of the Barabasi Albert network, which have undue influence on the early evolution of the network. They play lots of neighbors, which gives them very high scores, letting them propagate their strategies to their many neighbors. This noisy signal drowns out all the other effects.

Having found that simple explanations and random effects can explain most of the behavior here, I extend the model to a “three bit” system, where the agents play two rounds against each neighbor and can choose their second play based on what their opponent played on the first round. Indeed, in all three models the effect of decision cost on cooperation is either less pronounced, gone, or reversed!

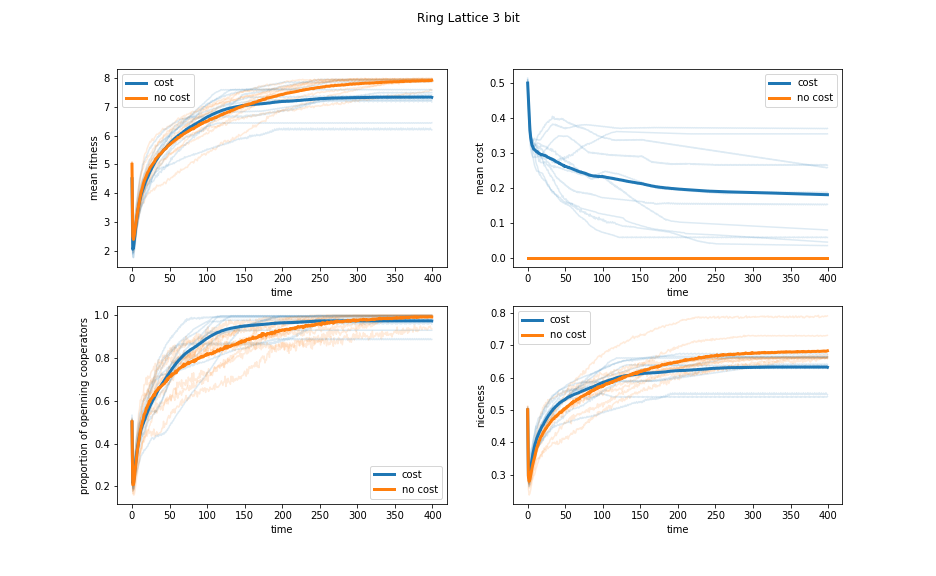

Figure 4: Evolution of the three bit ring lattice model with and without decision costs.

Figure 4 shows that the increase in the speed at which cooperation dominates with decision cost is less pronounced, and that the networks without cost are nicer on average than those with cost.

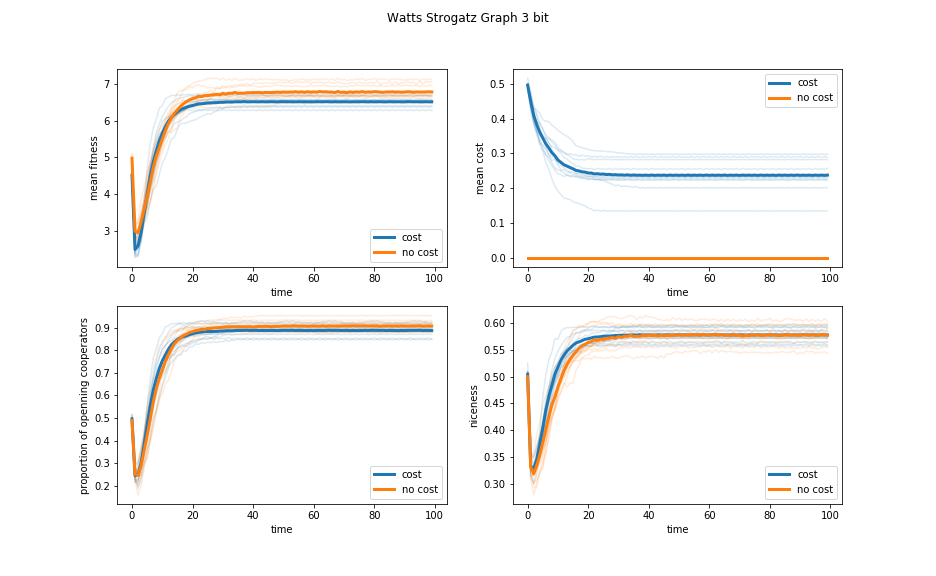

Figure 5: Evolution of the three bit Watts Strogatz model with and without decision costs.

Figure 5 shows that the average niceness at equilibrium is almost identical with or without decision cost, and that the networks without decision cost have slightly more cooperation on round one.

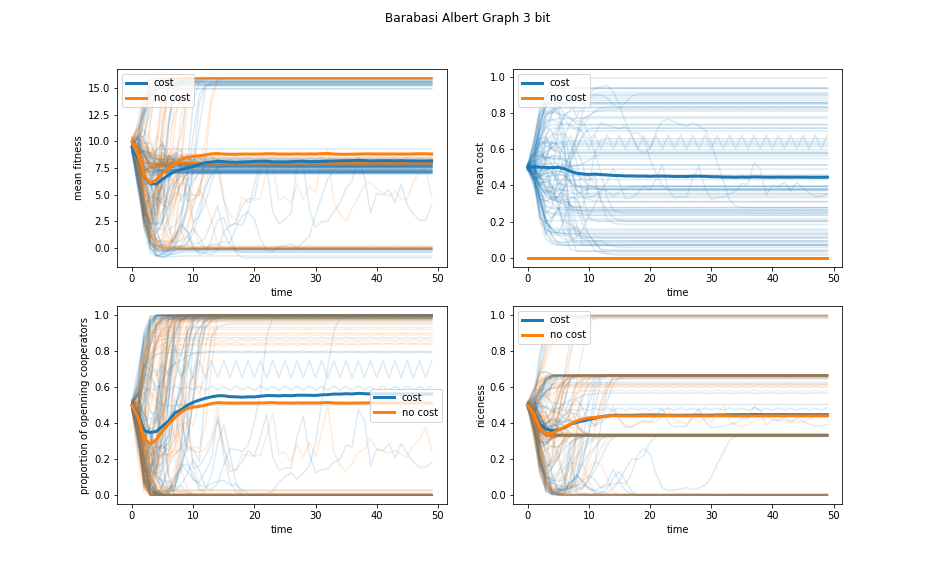

Figure 6: Evolution of the three bit Barabasi Albert model with and without decision costs.

Figure 6 shows that in the three bit model, Barabasi Albert graphs are still too unstable to draw meaningful conclusions from.

From these underwhelming results, I conclude that this effect is not stable enough to take seriously. Small changes in the experimental setup can destroy or reverse it. The fact that people take different amounts of time to justify their decisions is not enough to explain the social cooperation of evolution. For a more nuanced approach, I would want to run this model using Bayesian agents like the two arm Bernoulli bandit agent, to model the way people learn from experience. Bayesian agents get stuck in their ways once they are mostly sure of the truth, though, so it would also be important to model the way that people have to pass their knowledge on to future generations. The Barabasi Albert network provides a natural way for the network to grow and shrink, so that would be a good choice. Perhaps that model would be robust enough to use.

Works Cited

[1] Barabasi AL, Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 1999;286(5439):509-12.

[2] Ohdaira, T. Coevolution between the cost of decision and the strategy contributes to the evolution of cooperation. Sci Rep 9, 4465 (2019) doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41073-9. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-41073-9

[3] Watts, Duncan J; Strogatz, Steven H., Nature (Jun 4, 1998): 440-2.